2021 Vogue Japan: September Issue

We’re excited that Mariam has been featured in the September, “ Live Your Dreams” issue of Vogue Japan alongside other creatives from around the world.

The Prince Claus Impact Awards Jury

We’re proud to announce that Mariam will be part of the Prince Claus Impact Awards 2021 jury, an independent body that will select the Prince Claus Impact Award recipients.

_

The Prince Claus Impact Awards Jury

The jury is an independent body, comprised of five international and highly inspiring individuals. Representing diversity in terms of gender, geography, disciplinary specialism, each jury member brings distinct knowledge and unique perspective to the group. Together they select the Prince Claus Impact Award recipients based on a balanced and thorough selection process looking at the background, geography, gender, discipline and socio-political issues addressed through the nominee’s work. The five jury members will select the six Prince Claus Impact Award Recipients in 2022.

Alero Olympio Memorial Annual Lecture

Mariam Kamara will deliver the inaugural Alero Olympio Annual Lecture at the African Futures Institute in Accra on 19 August 2021.

Wanted Magazine: Africa Design Issue

We’re proud to be featured in South Africa’s Wanted Magazine’s July issue in an article titled “Celebrating the shapeshifters working at the forefront of African Design”.

2021 Spring Lecture at MIT Architecture

Mariam gave a talk at MIT as part of their Spring Lecture series. The talk is titled: "How we narrate our yesterday determines how we integrate the future of architecture"

Galerie Magazine's Creative Minds 2021

The list salute trailblazers who dare to dream big and push the boundaries of their respective fields to new heights.

The list salute today’s creative luminaries who dare to dream big and push the boundaries of their respective fields to new heights.

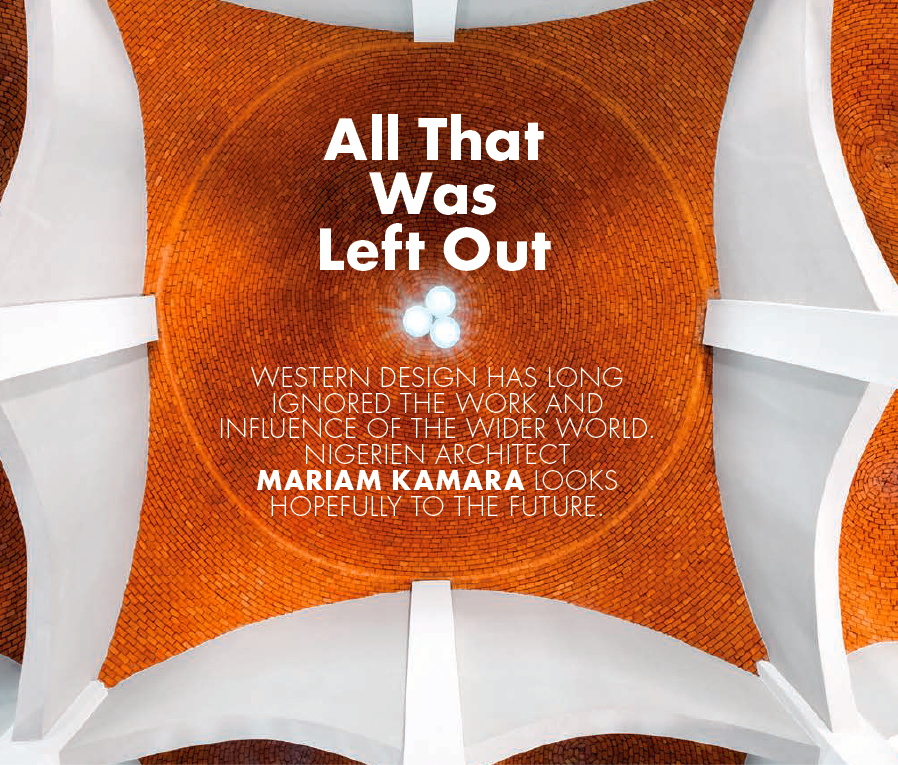

ELLE Decor: All that was left out

Western Design has long ignored the work and influence of the wider world. Mariam looks hopefully to the future

While I was in college studying computer science, before I decided to become an architect, I picked up a book by Patrick Nuttgens that confounds me to this day. It was called The Story of Architecture. Naturally, I expected it to be filled with awe-inspiring structures from all around the world, but most of it was focused on works from Western Europe and the United States. The rest of the world’s output became little more than a bonus track on a pop album. I was enraged. For a non-Westerner like me, it was profoundly humiliating. How could architecture from other continents, dating back thousands of years, be reduced to so few buildings, while Baroque churches got an entire chapter?

I have kept that book all these years, since becoming an architect myself, as a reminder that history truly is written by the victor and that the standard-issue perceptions of what makes a great building must change. My parents raised me in a small town in Niger, in the middle of the Sahara desert, where it was not uncommon to walk among centuries-old adobe buildings built by guilds of expert masons. On weekends we often took day trips to the nearby mountains to look at Neolithic cave drawings and admire the ancient polished-stone tools strewn on the ground. This experience is now impossible; most of the artifacts I encountered so casually then have since been “harvested” and sold to museums around the world. At the time, it felt as though we were living in history. These formative years continue to impact my work, in spite of the fact that I received my architectural training in the United States.

The callousness with which non-Western architecture and art are treated was something I would experience numerous times in magazines and at academic conferences. But this disregard was most glaring in how, as creatives, we are educated to take inspiration from precedents presented as universal masterworks that, in reality, only represent the perspectives of a small, homogenous group. What constitutes great architecture in the Western imagination is also a story about what is missing, what is being left out. I remember how baffled I was when I heard Niamey 2000, the first project I had ever developed, being assessed as a Bauhaus-style building. The real inspiration was traditional Hausa architecture dating back centuries, from places like Zinder and Agadez in Niger as well as Kano in Nigeria. The fact that it might remind one of a Bauhaus building should actually trigger a whole other conversation we are reluctant to have in architecture—one about the origins of many of the design shifts that occurred in Europe during its colonial dominion over Asia and Africa. Modernism and its aesthetic were not born in a vacuum from sheer genius, any more than modern art movements of the West, like Cubism, materialized out of thin air.

I often think about what could be learned from what is missing when our magazines and syllabi lean so exclusively on knowledge produced in Europe and North America. Long before the rise of European civilizations, ancient Asian, Middle Eastern, African, and South American architectures were already embedded with sophisticated solutions for addressing the challenges of their environments. Our focus on relatively recent—and often expertly edited—Western histories is at best a missed opportunity. The future presents challenges like the climate crisis, rapid urbanization, and demographic explosions for which we cannot consider real solutions until we decolonize our point of view. Until then, the decisions we make as designers will continue to be based on distorted narratives of who we think we are and what our past is. How we narrate yesterday determines how we imagine tomorrow. In this new year, it feels as though we are finally willing to listen to each other enough to seize a unique opportunity to design a future that will not be based on falsified or incomplete histories. We can choose to acknowledge the gaps and begin to fill them in so we have a chance to build a world based on something truer and, ultimately, richer. That will be the story of architecture.

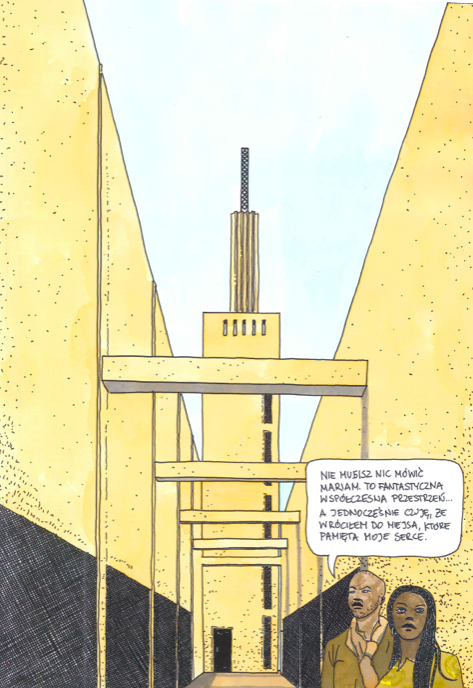

Architect makes comic book inspired by atelier masōmī

Architect Paweł Paradowski is was inspired by atelier masōmī’s to create a fictional comic book story.

A page depicting one of the scenes in Paweł Paradowski’s comic book.

Polish architect and urban planner Paweł Paradowski has been working on projects in places like Ghana and the DRC for a number of years. But his passion, when not working or travelling, is comic books. During a workshop in his hometown of Warsaw, he had to create his own fictional comic book story (in Polish) based on someone who inspired him. He decided to use it as an opportunity to combine all his passions of travelling to different West African countries and sustainable architecture and picked Mariam Kamara as the heroine in his fictional comic book. “For two years I have been working on a project to expand the city of Kalemie in DRC. It is an ambitious project in which I have to deal with many problems faced by the inhabitants. For this reason, I have been looking for inspiration from what is being created on the continent. This is how I found out about Mariam Kamara and atelier masōmī’,“ Paradowski says.

Paweł Paradowski’s drawing of Mariam Kamara and Sir David Adjaye

“Every year, comic book workshops are held in my city, Warsaw, devoted to personalities who have a great influence on the fate of various African countries and the world. This year, I was able to participate in it and I knew immediately who would be the heroine of my comic. The workshops are run by the Kultura Otwartości foundation and the mentor is Berenika Kołomycka, a great comic book artist.”

Paradowski says the story he came up with is loosely based on how he imagined Kamara and Sir David Adjaye meeting. While they met through the Rolex Mentorship programme in real life, in Paradowski ‘s comic book tale they meet in Niger where Kamara proceeds to show him around projects like the Dandaji Market and Hikma Religious and Secular Complex. “It is accompanied by drawings showing both the traditional architecture in Niger and the community functioning in the implemented design. The dialogues contained in them are ordinary conversations of the inhabitants. They relate to politics, sports or flirting (a young boy and girl in the library). At the end of the comic, we meet Mariam. On this drawing David compliments her work with words that I also made up.” He says the result of the workshops will be this story being included in a booklet containing the participants' works. He added: “It is published in Polish and available in my country at various African events”.

atelier masōmī makes it into the 2021 AD100 list

In the world of design and architecture, no list is held in higher esteem than the AD100.

In the world of design and architecture, no list is held in higher esteem than the AD100, now entering its fourth decade.

We are looking for junior, mid-level and senior architects

We are looking for junior, mid-level and senior architects to join our growing team in Niamey, Niger.

We are looking for junior, mid-level and senior architects to join our growing team in Niamey, Niger. Please send your applications to recruitment@ateliermasomi.com

Junior Level Architect

The ideal candidate will be a driven and self-starting individual.

The candidate needs to have at least 1 year of post-qualification experience.

They must have sound technical knowledge and excellent presentation skills.

The candidate must be capable of adapting and adding value in a diverse environment.

Candidates must be able to produce construction documentation.

They must be highly proficient in Archicad, SketchUp and AutoCAD.

Having 3D rendering skills would be advantageous to your application.

Mid Level Architect

The ideal candidate will be a driven and self-starting individual.

The candidate needs to have at least 4 to 5 years of post-qualification experience.

They must have sound technical knowledge and excellent presentation skills.

The candidate must be capable of adapting and adding value in a diverse environment.

Candidates must be able to produce construction documentation.

They must be highly proficient in Archicad, SketchUp and AutoCAD.

Having 3D rendering skills would be advantageous to your application.

Senior Level Architect requirements

The ideal candidate will be a deadline driven and self-starting individual with at least 7 years of post-qualification experience.

The candidate must be capable of adapting and adding value in a diverse environment.

The candidate must demonstrate excellent technical knowledge in their application.

The candidate must be highly proficient in Archicad, SketchUp and AutoCAD.

The candidate should be capable of managing every stage of a project under pressure from inception to completion.

Traveller Pierre Yuan visits Dandaji Market and Hikma

Yuan, who moved from China to Benin a few years ago, shares images and thoughts on his recent trip to see our projects in the village of Dandaji.

it is always really heartwarming when people show appreciation of our work. But this is a first for us. Pierre Yuan is a Chinese teacher and traveller who has been working in our neighbouring country, Benin, for the past few years. Upon coming across our work he decided to travel to the village of Dandaji so that he could view the Hikma Religious and Secular Complex as well as the Dandaji Regional Market with his own eyes. He shared some of the pictures from his travels with us as well as his thoughts on the project.

An avid cyclist, Pierre once travelled by bike from Benin to China, which took him one year and a total distance of 16,000kms. He says: “I just wanted to show my people how Africa is. After staying several years in West Africa, I know that the world is not what we have seen from internet or media. We had better discover with our own eyes. I, personally, had no problem when I cycled through 11 African countries. But how about the news from the media? Ebola? Malaria? illegal immigration? Robbery? No, there are so many amazing things we haven't found in this continent. Seeing is believing.”

Hikma Religious and Secular Complex is a site where a derelict mosque was turned into a library that shares its site with a new mosque in the village of Dandaji in Niger. Picture by Pierre Yuan.

The project is a culture and education hub where the secular and the religious peacefully co-exist to cultivate minds and strengthen the community, which has a very young population of 3000 people. Picture by Pierre Yuan.

“ The mosque is spectacular. The masomi team once again used the most basic and original materials of the land to create a specific traditional structure and system. The shape and colour of the mosque makes it unique in the world. More importantly, it is friendly to the locals. It’s not a show.

”

The main goal of the Dandaji Regional Market was to create a space that projects a sense of confidence and aspirations for the future in the users. Picture by Pierre Yuan.

The project design references the area’s traditional market architecture of adobe posts and reed roofs, pushing the typology forward using compressed earth bricks and metal for durability. Picture by Pierre Yuan.

Lexus Design Awards 2021 names new mentors

Mariam joins a line-up of judges and mentors who will support up-and-coming creators for a Better Tomorrow.

The lineup of judges and mentors will support up-and-coming creators for a Better Tomorrow.

New York Times' 15 Creative Women of Our Time

Eschewing a Western definition of modernity, Mariam Kamara instead conceives of buildings and spaces that account for how people really live.

Eschewing a Western definition of modernity, Mariam Kamara instead conceives of buildings and spaces that account for how people really live.

Mariam Kamara on the cover of Gray Magazine

Architect Mariam Kamara, founder of Atelier Masōmī, is redefining architecture in her home country of Niger.

Drawing inspiration from her childhood in Niger, architect Mariam Kamara is addressing the political nature of public space while reclaiming the Nigerien architectural vernacular.

atelier masōmī featured in Architectural Digest India

Under the auspices of Rolex, Mariam Kamara and David Adjaye plan a cultural complex in Niger.

Under the auspices of Rolex, Mariam Kamara and David Adjaye plan a cultural complex in Niger

Beyond the West - New Global Architecture

We’re delighted to be included in this book that inspires a fresh understanding of global contemporary architecture in Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

Text from from Gestalten:

In the last decades Western architecture has largely dominated the discourse and the built environment worldwide. Recently architecture firms from non-Western countries have been establishing local and global recognition for themselves. Practices all over the world face challenges against a backdrop of rapidly growing cities, ecological demands, changing societies and climate, and emerging economies. Local architects often find strikingly different solutions to local requirements, including sustainability, transportation, migration, construction materials, and traditions.

In Mexico, architects work closely with indigenous communities to create modular social housing that can be assembled in one week. In Namibia, a lodge in a wildlife conservancy is designed to echo a local bird’s nest, while in Vietnam, a library and public space have created a micro-ecosystem to house fish and grow food.

Beyond the West journeys across Asia, Africa, and the Americas to understand how local architects respond to a changing world, and focuses its wide lens on inspiring and truly global architecture.

A young architect reflects on graduating in 2020

What is it to be a fresh architecture graduate faced with a world filled to the brim with imbalances, uncertainty and questionable realities?

Graduating in our dormitory’s courtyard. ©Mariama M.M. Kah

What is it to be a fresh architecture graduate faced with a world filled to the brim with imbalances, uncertainty and questionable realities? Surviving architecture school was no easy task. We all know what it took to survive it. Feeding into the often problematic and demanding work culture of architecture schools, I spent countless sleepless nights glued to my files adjusting my drawings. When sleep visited me, the work that remained would intrude my dreams; beckoning me to return to it. I doused my aches in copious amounts of caffeine, sped between prints and re-prints upon discovery of flaws. I used the most delicate of touch, concentrating all my focus, on my models during their assembly... the list goes on. Despite how I dealt with it, surviving architecture school was no easy task and it demanded much of myself to endure and excel.

It’s completion was not with the fanfare we all deserved and longed for. Graduation, a day we had spent years striving towards, amounted to a nod of acknowledgment in a hastened online ceremony at its most, and an online transcript at its least. My achievements paled in grievous comparison to the current state of the world in the sphere of health, politics, and race relations. With our current reality growing more complex by the day, it is all too easy for those of us fortuitous enough to be members of the “Class of 2020” to slip into a mournful and depreciative state: interrogating our place in this world, and our significance as we seek to begin our journeys as architects in our respective societies.

What is it to desire to fill the role of builders in society when we can see so many of its cracks begin to chip and crumble?

I want to become a space-maker. One that will create the physical realities of the world I wish to inhabit: the schools and libraries where great minds will be nurtured, the museums and cultural centers where the traditions of a people will be preserved and celebrated, the many houses that loving families might one day build lives in and call homes... I want to be the kind of architect who amplifies the lived experiences of the people I make spaces for. These prospects are what drew me to architecture and are what I cling to, now more than ever.What is it to have the added dimension of being a young “African” architect?

The Acropolis in Athens and The Great city of Benin. Courtesy of Creative Commons and The Guardian.

Honestly, I am trying to come to an answer to this question myself.

I, like many others, did not receive my architectural education on the continent. But I possessed a deep desire to return and have a part, no matter how small, in constructing its future.

I found myself in one of many architectural institutions that bases its curricula on Western and European models. I was lectured on the many virtues and the architectural significance of the Acropolis in Athens and taught to commit to memory the Roman orders. But I was taught nothing about the Great City of Benin and the precision of its walls. One of the greatest capitals in precolonial West Africa, with possession of a wall that surpassed the Great Wall of China in length (four times over), with a dexterity and finesse in its city planning worthy of global admiration; formed no part of my syllabi.

My professors presented the architectural champions and heroes to me. I dedicated myself to dutifully memorizing their names and that of their works: Le Corbusier and his Villa Savoye, Mies Van der Rohe and his Barcelona Pavilion, Frank Lloyd Wright and his Fallingwater.

This was to be my canon.

This was to be my “well of inspiration” as I sought to design my own projects. In many ways it is and forms the foundation of the things I have come to know about architecture. But this canon did not root itself in the realities of the Global South, nor did it make much efforts to seek and cherish the parts of the continent I held dear.

Barra Port Town near the border of Senegal and The Gambia. ©Mariama M.M. Kah

Seeking “wells of inspiration” as a young architect.

This “well of inspiration” is one that I knew that I had to consider deeply.

The one I was presented with would not suffice alone nor would it meet the lofty demands of my vested interests. I knew that I had to dedicate myself to consistently work to incorporate knowledge of the continent that I hoped to one day return to and build for. This reservoir of admiration would have to be constructed on my own, brick by brick.

It started first with engaging with as many stories from the continent I could manage. I had always believed that architects had a strange and beautiful role in choreographing the stories of our lives. I remember tearing through Penguin’s African Writer’s series all through my adolescence. Learning the dance of the lives I wished to choreograph. I commit much time and interest to learning as many corners of the continent as I can through novels, films, articles, histories, and music.

Visits to my father’s village, Amdallai (which is located at the border of Senegal and The Gambia) sparked interest into learning more about vernacular architectural practices of the region and beyond. We would cross the river on ferryboat, the capital with its mid-rise building and aging infrastructure slipping further into the distance and drive the rest of the way down. The narrow tarmac road was the only thread connecting the small towns and villages gleaming in corrugate and concrete, along the way. With a large expanse of farmland in between, earthen structures dotting their fringes. The air was always lighter here and I grew curious of it all hearing my uncles beam at their preference of concrete walls that left them hot and sweaty during the raining season over the earthen walls that kept them cool on their farmlands during that same time.

And so, I grew in admiration of the purveyors of vernacular traditions: the masons, carpenters, and artisans; often nameless entities that posses a deep understanding of the very marrow of what is at the built culture’s core.

I then began to seek out my own architectural champions and heroes. Those who were doing the work that I admired on the continent and across the world. I taught myself their names and that of their works: Diébédo Francis Kéré and his Gando Primary School, Sir David Adjaye and his Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, and Mariam Kamara and Yasaman Esmaili’s Hikma- Religious and Secular Complex.

I married what lessons I could to the work I did in school.

A corner in my grandfather’s compound at the border of Senegal and The Gambia, Amdallai. ©Mariama M.M. Kah

The urgency to fill in the gaps of my education and add depth and dimension to my “well of inspiration” is one I think many young African architects can relate to.

As young African architects, we are acutely aware that the future for our cities and countries are often presented as faceless non-specific utopias. Adorned with glass towers gilded in steel, with high speed highways and overpasses that loop across the landscape like tar ribbons, that could find itself in any industrialized city of the world.

It is deemed “modern” by politicians, developers, or wealthy men and drapes itself in imported aesthetics, begging to be called by the name “progress.”

To be a young African architect, I believe, is to question this and seek out threads and instances where we can identify and remember ourselves; and think towards tailored and responsive architecture that considers our nuanced cultural realities.

In our collective journey of “becoming,” it might be time to engage in an unyielding investment of time and education to cultivate an intricate understanding of the unique complexities of our individual pasts, intertwined present realities, and projected futures.

I would like us to consistently strive to take ownership of our “wells of inspiration,” to construct and perpetually expand them —brick by brick—so we may one day build a new present reality in our own image, and no one else’s.

Our well of Inspiration must be ever, expanding. Courtesy of Creative Commons

Dezeen's 2019 Design Virtual Festival

Mariam spoke in a live conversation with Dezeen’s editor-in-chief, Marcus Fairs, as part of Virtual Design Festival.

She spoke to Dezeen editor-in-chief Marcus Fairs in a live Screentime conversation as part of Virtual Design Festival. Running from 15 April to 10 July 2020, the festival was the world’s first online design festival.

Lecture at the University of Johannesburg

Mariam Kamara was invited to give a talk at the Graduate School of Architecture (GSA) in Johannesburg, South Africa

Mariam Kamara was invited to give a talk at the Graduate School of Architecture (GSA) in Johannesburg, South Africa. The GSA at the University of Johannesburg was founded in 2015 with a simple mandate: to transform contemporary African architectural education. Mariam spoke about her studies in the US, her work since founding the firm in 2014 and more.

Join the team!

We are looking to hire three architects to join us at our office in Niger’s capital, Niamey.

atelier masōmī is seeking to hire a senior architect in our Niamey Office:

𝐒𝐞𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐫 𝐋𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐥 𝐀𝐫𝐜𝐡𝐢𝐭𝐞𝐜𝐭

𝐑𝐞𝐪𝐮𝐢𝐫𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐬

The ideal candidate will be a deadline driven and self-starter with at least 7 years of post-qualification experience, capable of adapting and adding value in a diverse environment. The candidate must demonstrate excellent technical knowledge in their application and be highly proficient in Archicad, SketchUp and AutoCAD. The candidate should be capable of managing every stage of a project under pressure from inception to completion.

Kindly send your application (CV + portfolio in .pdf format no larger than 5MB) to:

recruitment@ateliermasomi.com

We look forward to hearing from you!